Round Trip

I flirted with golf through my first twenty-one years growing up in Hendersonville, North Carolina, and matriculating at the University of North Carolina, but it was not until taking a physical education class in the sport my last semester in Chapel Hill in 1979 that I gave serious thought to pursuing the game with any degree of consistency, passion and focus. My first job was with the Asheville Citizen-Times, and with working mostly evenings for a morning newspaper, I had my days free.

So I played golf.

Several guys from the sports department and a handful of others scattered throughout the building gathered at various courses in the area early in the morning, played eighteen holes, then showered and hustled to work.

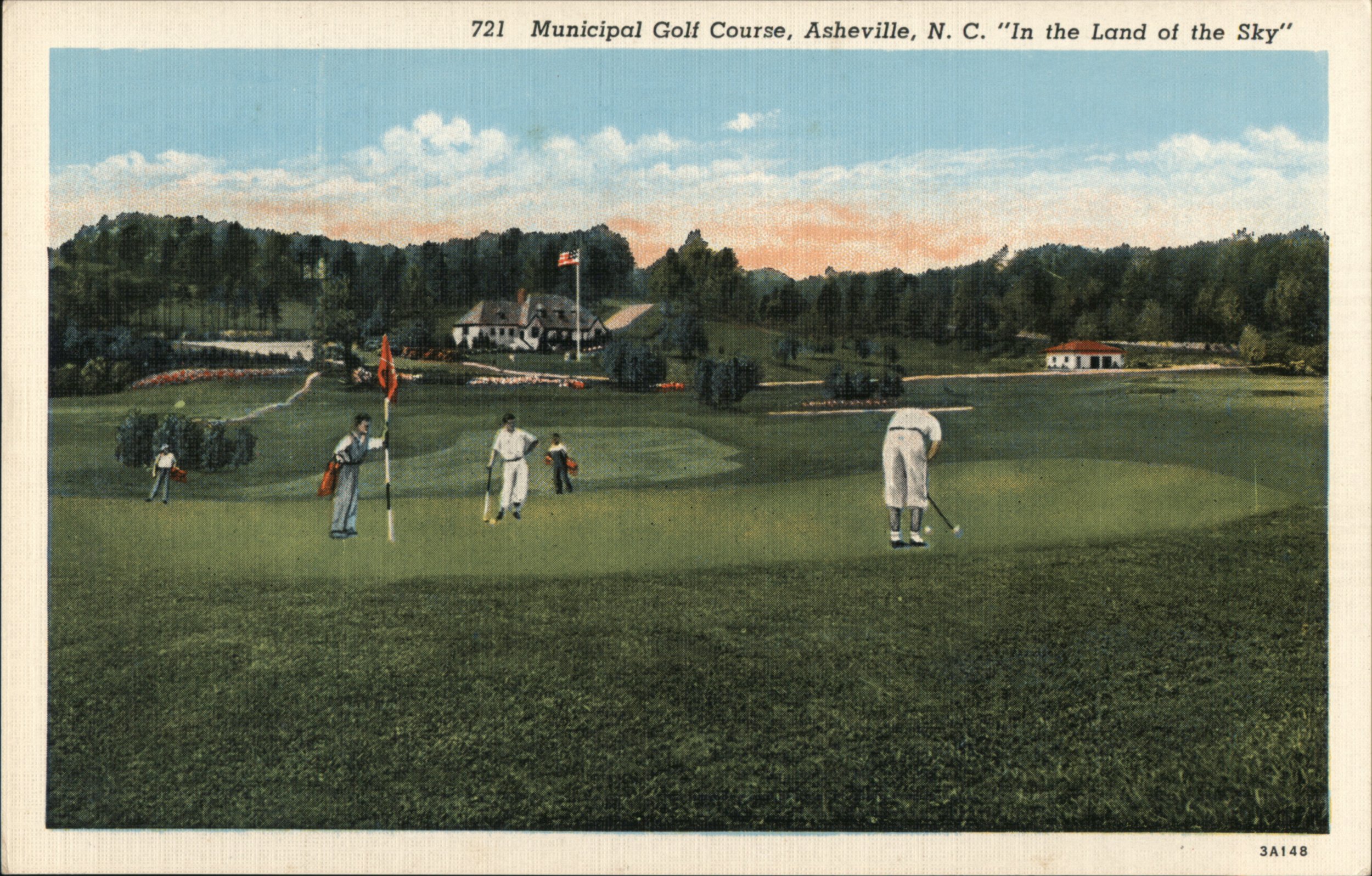

Asheville Municipal Golf Course was one of our regular stops.

Usually they’d let us go off the back nine to avoid the dew-sweepers on the front side, so the first two holes plus getting to the twelfth tee were straight uphill, the back nine winding through stark elevation changes in the Beverly Hills neighborhood and the front nine on flat-as-a-pancake ground between the clubhouse and the Swannanoa River.

Your heart's pumping after climbing to the green of the par-four 11th hole; the back nine winds through the steep topography of the Beverly Hills neighborhood.

At the time I was slinging some Wilson Staff irons I’d bought back in high school after earning the money by detasseling corn for two weeks in the hinterlands of Henderson County. I had no taste for apparel (kilties on saddle shoes were de rigueur for the day) and I had no appreciation for the architectural nuances nor the history of the great designers. But over four decades of generating hundreds of magazine articles and blog posts and several dozen books in the golf world, the story of the Muni and its 1927 opening has sunk in.

It was one of four courses designed and built in Asheville in the 1920s by Donald Ross, the Scotsman who had immigrated to the United States in 1900 to forge a career in a sport just beginning to take root in America. He designed Biltmore Forest Country Club (1922), the Omni Grove Park (1926, originally known as Asheville Country Club) and the Country Club of Asheville (1928, originally known as Beaver Lake Golf Club before the country club bought it in the mid-1970s, moved a mile and a half north and changed its official name for legal purposes). I challenge you to find another town with as many still-intact Ross courses within a seven-mile axis.

It was built without heavy earth-moving machinery, so Ross made do with what he had to work with—up a valley, down a valley, balls bouncing right-to-left on one canted fairway, left-to-right on another, massaging the flatter areas with one green built on a ledge and bunkers in the corners of doglegs on others to vex the aggressive player.

The original layout of the Asheville Muni had the nines reversed; the front nine later became the holes along the Swannanoa River.

It was one of two major municipal projects that Ross took on in North Carolina’s bookend, mountains-to-the-coast cities of Asheville and Wilmington. The Wilmington course opened a year earlier and both were hailed by Ross as templates for the coming wave of public courses.

“The development of municipal golf courses is the outstanding feature of the game in America today,” Ross said. “It is the greatest step ever taken to make it the game of the people, as it should be. The municipal courses are all money makers and big money makers. I am naturally conservative, yet I am certain that in a few years we will see golf played much more generally than is even played now.”

The Muni was the home course for young African Americans who caddied at other clubs in town but could play the Muni on Mondays and was where a golfer like John Brooks Dendy played with homemade clubs made of discarded clubheads attached to broom handles and honed his razor-sharp short game before winning three National Negro Championships in the 1930s. It’s where Dendy could meet a boy whose father owned a blanket factory and lived in the opulent Biltmore Forest neighborhood and give a golf lesson; Charles Owen Jr. would use those skills to post multiple low sixties rounds at Biltmore Forest.

“Brooks could have been a PGA Tour star,” Owen says. “He was the best putter I have ever seen. There is no one out there today that can touch him. When I first started with him, all we did was the short game. He always said if you can hit a wedge and hit it properly, you can score. He said tee shots are for people to awe over. But wedges are for people to win with. I’ll never forget that comment. It’s just as true today as it was then.”

Lee Elder won four straight Skyview Opens in the 1960s before moving on to a long career on the PGA Tour.

It was the Muni where, after the landmark ruling of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 effectively ended the Jim Crow era of “separate but equal” public facilities, that play began to be fully integrated. A tournament called the Skyview Open was launched in 1960 (and continues today every July) to help launch aspiring young Black golfers into professional golf, with Lee Elder winning four straight Skyviews from 1962-65 and players like Jim Thorpe, Jim Dent and later Harold Varner III teeing it up over the years as well.

It was a place where the game could be celebrated and embraced, no matter your bank account or blood lines, where golfers played with their shirttails out and ball caps on backwards, where the tees were often a little bare and the fairways splotchy. No one enjoyed the game more than Billy Gardenheight and the course’s long-time starter, Cortez Baxter.

“Golf is like drugs, it’s addictive,” says Gardenheight, a Skyview champion and Muni regular. “You can play from cradle to graveyard. Most sports you have to give up. This one you play as long as you want to.”

“It’s like sex—you don’t have to be good at it to enjoy it,” adds Baxter, a long-time starter at the Muni who still shows up regularly at age ninety-five to chip and putt and chew the fat. “Once you pick up the clubs, that’s it. You’re done for.”

***

All of these elements coalesced in 2002 to prompt a group of concerned citizens to submit an application for the Muni to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The facility is located on Swannanoa River Road less than a mile from the location of a Wal-Mart Supercenter on the drawing board at the time, and neighborhood residents and concerned golfers worried that the front nine could be chopped up if the two-lane road were widened to accommodate traffic. The application was approved in April 2005; the road remains intact at two lanes.

Fortunately, the bones of the golf course are locked down as well and are in the midst of a $3.5 million renovation and restoration via city funds, user fees and grants. A big chunk of the project concerns stormwater and irrigation management and repairing infrastructure that has deteriorated over a century, but tees, greens and bunkers are getting work and the pro shop has been renovated. Architect Kris Spence, who’s developed a niche over twenty-five years restoring Ross courses, was hired via funds from The Donald Ross Society to provide a masterplan (though he is not hands-on in supervising and managing the work).

The first phase of the project started in October 2022 and will run through the fall and winter of 2023-24, when the bulk of the underground piping and drainage work will ensue.

“We’ve gotten so many good comments from regulars who cannot believe the transformation,” says Pat Warren, the head golf professional since 2016. “It’s nice to work at a course where there’s a lot of excitement over what’s happening now and what’s to come.

“The drainage and irrigation is old, to say the least,” he continues. “The layout is still pretty close to Ross’s original vision. The biggest piece beyond the water management is getting the tee boxes back in good shape, leveling them in places, resodding in places. We’re addressing fairways where they’re thin.”

One of the most significant changes to the course is the 16th hole, where the fairway and green have been resodded and new bunkers built around the putting surface.

“It’s been glorious to watch,” adds Phil Blake, who grew up in a house on the tenth fairway and has played the course for more than fifty years. “I never in my lifetime have seen this much money thrown at this golf course. There were periods of time when the superintendent might rebuild something, but to have new sod? That’s country club type stuff.”

City of Asheville officials have taken note in recent years of significant restoration projects at other municipal courses, most notably the very Wilmington layout that Ross built in 1926 and the Charleston Municipal that opened in 1929.

Wilmington Muni GM and pro David Donovan led an effort in 2013-14 to hire architect John Fought to supervise a renovation that included building new greens complexes, bunkers and putting surfaces and planting them with Mini-Verde Bermuda grass, twenty-four new/rebuilt tees, some tree removal to improve sunlight and air flow, and the removal/repositioning of cart paths in some areas at a cost of $1.5 million. Another $1.1 million was spent in 2021 to renovate the clubhouse. Charleston shut down one nine at a time beginning in December 2019 to hire architect Troy Miller to coordinate fixing drainage problems, reshaping tees, fairways and greens and removing some trees to promote healthy turf growth. The city paid the $3 million tab with half recreation bond funds and the other half from a private fundraising drive.

“On Mondays now when the private clubs are closed, we’re getting players from Porter’s Neck, Landfall and Cape Fear,” Donovan says of the Wilmington golf market. “This meets their standards now. That’s a big deal.”

More catalysts evolved in Asheville when operation of the Muni moved into a new division of city management in 2022 and the city struck a deal that autumn with a new outside management firm, Commonwealth Golf Partners II, a partnership between long-time industry professionals Peter Dejak and Michael Bennett. In January 2022, the city’s golf course, tennis courts, soccer park, Nature Center and McCormick Field baseball park came under the auspices of Community and Regional Entertainment Facilities for the City of Asheville and within the umbrella that also included the downtown concerts/sports arena and performing arts theater.

“It was obvious the course had gotten into bad shape,” says Chris Corl, the director of the newly created department. “The relationship with the previous operator had soured. The lease was coming up. We had to do something. If we were to get a new operator and an operator of substance, we had to do something significant with the golf course. Otherwise we would still have a course with more dirt than grass.”

A $1 million commitment from the city combined with matching grants from other sources and private donations gets the project close to its Phase I goal of $3.5 million. Fund-raising is ongoing, and the Friends of Asheville Muni was launched as a 510(c)3 organization to help generate money to continue the restoration well into the future.

“Every time I go down there, I meet new people who say, ‘I can’t believe this is happening here,” says Corl, who lives in the Beverly Hills neighborhood. “The tried-and-true regulars are ecstatic. The next step is to get the out-of-market visitor to play during tourist season, get good reviews and grow that business. That’s what will allow us to reinvest—getting visitors to play the course, enjoy it and come back.”

The interior of the pink granite clubhouse designed in the Tudor Revival style has been renovated with new merchandise heralding the Donald Ross name and 1927 opening date. On management’s wish list for down the road is enough money to restore the hip slate roof and dormer windows that were lost in a 1956 fire. New tee signs and pin flags have been designed, fabricated and installed.

The complex for the first green signals that things are different now at the Muni. Flanking the putting surface are grass hollows, bumps and long, wispy grass, sort of a Pinehurst effect as indicated on Ross’s original blueprint. The bent/poa greens are in good shape and are now getting more fine-tuned maintenance attention with new equipment and manpower. Emblematic of the work is the par-four sixteenth, where trees have been pruned to open sunlight, parts of the fairway sodded, the green almost totally resodded and new bunkers built around the green.

Standing on the terrace overlooking the front nine, Warren looks at the third green and sees a maintenance worker walk-mowing the perimeter of the green.

New pin flags and tee signs pay tribute to designer Donald Ross, whose thoughts on the importance of municipal courses are displayed on a plaque outside the clubhouse.

“The other day I saw three workers on one green,” he says. “I stopped and thought, ‘I’ve never seen three guys in one place before.’ It’s nice to have the staff to get things done, not to mention some new equipment. We’ve never walk-mowed a green before.”

Blake remembers as a boy hunting for golf balls in the woods between the houses and fairways and selling five balls for a quarter back to golfers. He started playing at a young age and in high school was featured in the Asheville Citizen-Times after shooting a sixty-three. He’s lived in East Asheville all his adult life and has played most of his golf at the Muni.

“There’s a new spirit around here, for sure,” he says. “This isn’t the hardest course in the world, it’s not very long and there’s no room to lengthen it. But the par-threes from the blue tees are just fantastic. I can’t imagine a stronger set of par-threes anywhere. From the blue tees, you’ve got four holes over 200 yards long. I love that.”

Eighteen is a one-shotter falling sharply downhill, the length measuring 222 yards from the back tees but the variables of elevation, wind and air thickness from morning to late afternoon playing havoc with distance estimates. One of the city’s many surrounding mountain peaks looms in the distance toward the east.

I’m standing there one twilight in May 2023, having hooked up with a couple of regulars who live and work in the area. My mind drifts back forty-four years to having first played the course in the summer of 1979. The first domino to my life in golf fell somewhere between making a birdie and winning a skat and slinging verbal turds at the guys I was playing with. Then as now I schlepped my bag, certainly at the time because my $165 a week paycheck wouldn’t accommodate the cart fees and now because, well, that’s just the way the game’s meant to be played. Those dominoes have taken me to the Masters and the U.S. Open, to St. Andrews and Lahinch and Casa de Campo, to the offices of Ben Hogan and Arnold Palmer and Tom Fazio.

The quality of my golf on this particular day was putrid at best, given I was making baby swings in nursing a mild rotator cuff injury. But as I divined long ago and spent more than 200 pages explaining in my 2021 book, Good Walks, it’s not as much about the shots as it is taking one step at a time, ingesting the sights and making some golf small talk along the way. My Asheville Muni experience was terrific, remembering long-ago mornings and taking heart at seeing the course getting a much-needed injection of resources.

The highlight was the last hole, that par-three tumbling off the mountainside. I hit a twenty-one degree hybrid that hung in the air, bounced and rolled ten feet from the pin. The happy ending, of course, was my putt rattling dead into the hole.

More detail on the Asheville Muni restoration can be found here, and to make a contribution to the Friends of the Asheville Muni, click here.

Chapel Hill-based writer Lee Pace has written extensively about Donald Ross, Pinehurst and golf courses across the Carolinas and beyond since the 1980s. His most recent work is “Good Walks—Rediscovering the Soul of Golf at Eighteen of the Carolinas’ Top Courses,” available from UNC Press and Amazon.

This original layout of Asheville Muni and the surrounding Beverly Hills community had the nines reversed;